|

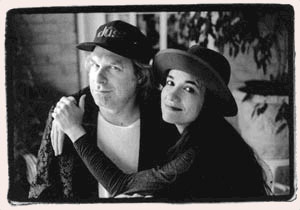

Song Review by Lou Wigdor Musicians in Rachel's

Grace |

You

have to wade ten songs deep into Buddy and Julie Miller’s new Grammy

nominated album, Buddy and Julie Miller (Hightone), before you

encounter Julie’s revelatory song, Rachel. It is a song of

uncommon spiritual intensity and purpose; a song that seems to

resonate right off the CD with a life force of its own. “After

reading Rachel’s spiritual biography, Rachel’s Tears

(authored by her parents, Beth Nimmo and Darrell Scott), I had a

burning passion, a compulsion, to write the song. The trouble was, I

just didn’t feel worthy,” Julie confessed in an interview with

this writer. Seventeen-year-old Rachel Joy Scott was the first of

thirteen high schoolers gunned down in the April 29, 1999 Columbine

High School tragedy. According to family, friends, and her own

personal journals, Rachel was an unassuming Christian of extraordinary

faith, grace, and compassion -- an outstanding student, artist, and

dancer, whose You

have to wade ten songs deep into Buddy and Julie Miller’s new Grammy

nominated album, Buddy and Julie Miller (Hightone), before you

encounter Julie’s revelatory song, Rachel. It is a song of

uncommon spiritual intensity and purpose; a song that seems to

resonate right off the CD with a life force of its own. “After

reading Rachel’s spiritual biography, Rachel’s Tears

(authored by her parents, Beth Nimmo and Darrell Scott), I had a

burning passion, a compulsion, to write the song. The trouble was, I

just didn’t feel worthy,” Julie confessed in an interview with

this writer. Seventeen-year-old Rachel Joy Scott was the first of

thirteen high schoolers gunned down in the April 29, 1999 Columbine

High School tragedy. According to family, friends, and her own

personal journals, Rachel was an unassuming Christian of extraordinary

faith, grace, and compassion -- an outstanding student, artist, and

dancer, whose  deepest desire (in Julie Miller’s words) was to be

a friend to the friendless, to know God, and to show love to everyone

she touched. “For a teenager, she had an extraordinarily mature

faith and an intimate, tangible connection with God,” Julie emphasized. deepest desire (in Julie Miller’s words) was to be

a friend to the friendless, to know God, and to show love to everyone

she touched. “For a teenager, she had an extraordinarily mature

faith and an intimate, tangible connection with God,” Julie emphasized.Can humankind commune with the divine? If you accept that possibility, you’d be hard-pressed after reading Rachel’s Tears to doubt that Rachel had some sort of dedicated broadband line to the celestial. That, however, brought with it bad news as well as good. “Her journals make it clear that she had premonitions about her fate,” Julie insisted. Inside her recovered backpack (with bullet hole), the final page of her journal revealed a drawing of her eyes with thirteen clear tears falling upon a rose and assuming its color as they continued their decent, Julie continued. A second journal, recovered later on, revealed another drawing of the same rose growing up out of a columbine plant containing the words: Greater has no man than this, than a man would lay down his life for his friend. Jeepers creepers. What chilling imagery -- imagery that Julie Miller incorporates seamlessly into her hymn (calling it a song doesn’t really do it justice).

But Rachel, like so many of Julie Miller’s creations, is ultimately about redemption. In a growing body of exceptional art songs (some with a touch of twang), her conflicted, sometimes downtrodden characters and the songs that they inhabit invariably work through their obstacles to achieve spiritual release. In By Way of Sorrow (on Blue Pony [Hightone]), her subject’s welcome at God’s table was predestined: “You have come by way of sorrow; you have come by way of tears. But you reach your destiny; Meant to find you all these years.” In Run Free ( on Broken Things [Hightone]) -- a musical masterpiece that deploys almost the same instrumental forces as Rachel -- Julie Miller has seen her subject’s dreams get broken. “But in my heart I see you run free. Like a river down to the sea.” Rachel, like every other Julie Miller character, is welcome at God’s table. But no Julie Miller song has ever radiated Rachel’s sense of urgency. Indeed, Rachel carries the cross of martyrdom. “She was singled out by the boys who murdered her because she was a good Christian in the best sense of the term,” Julie explained. “I don’t cry very easily, but this was a book I wept through from beginning to end.” Given Rachel’s unassailable spirituality, and Julie’s alchemic craftsmanship of deliverance, Rachel’s outcome was never in doubt.

The music itself is a perfect partner in this transmutation. From its first note, Rachel’s vibrant tempo (the second fastest on the eleven-track CD), conveys a confident, self-propulsive energy that drives the song throughout its three minutes and forty-two seconds. After a chorus-long guitar intro, the Millers’ hand-in-glove vocals (in both unison and harmony) lay down the two stanzas excerpted above with conviction and selflessness. Then the intensity level builds with a responding chorus that features the Millers’ voices with full complement of guitar, electric guitar, Hammond B3 organ, and bouzouki. The voices, which enter on higher ground at the dominant, ask Rachel a litany of questions:

We know the answers to those questions

intellectually. But we need the instrumental passage that follows to

complete the arc of belief both emotionally and spiritually. Emerging

from the instrumental fabric, now minus the voices, Buddy offers up

two lines of intertwining electric guitar filigree -- the first of sturdy

timbre and the second higher and brigh “We wound up rushing the album to get it out before we went on tour last summer,” noted Julie. That didn’t apply to the labor of love that is Rachel though, which got all the time and attention that it demanded. “I kept tearing the song apart. We redid it again and again instrumentally. I would sing the notes for the instruments to play. We kept trying different combinations until it all gelled. When I write a song, the music and the lyrics have to fit exactly. Lyrically, I could have gone different ways with the song. Lines got left out that didn’t quite fit.” For the Millers, studio time has never been an issue. They record all their albums in the living room of their hundred year-old house several blocks from downtown Nashville. Touring, however, has been another matter. During the past year, Buddy Miller has been in almost perpetual motion. When he’s not on the road with Julie, he’s playing bigger gigs with Emmylou Harris, as her guitarist and band arranger. His masterful guitar work is controlled intensity and risk taking informed by musical grace. In 1999, he received the Nashville Music Awards guitarist of the year honors. (After a much deserved week off from their own tour, Buddy and Julie joined forces on January 25 with Ms. Harris as her backing band for an eighteen-city Brother Where Art Thou tour with Alison Kraus, Ralph Stanley, Patty Loveless, and others.) “Julie and I made our own album on my days off,” Buddy remarked. “I’d come off the road, do my laundry, and record for a few days. It took us two years to rush out that album.” Buddy & Julie Miller is on track to outsell all of the Millers’ previous albums. (All have been issued under their separate names, but are, in varying degrees, Buddy/Julie collaborations.) The new CD has all the virtues of its forerunners: craftsmanship in writing and musicianship; seamless vocal duets; and less-is-more, organic arrangements. Like its predecessors, Buddy & Julie Miller’s broad brush of songs includes country and folk ballads, country rock hybrids, and Julie’s own special brand of non-urban art songs. (Buddy is also an increasingly prolific song writer. Lee Ann Womack, Brooks and Dunn, and Hank Williams III, and the Dixie Chicks have all recorded his work.) In concert, the Millers serve up the same varied fare, but with an important difference -- they favor a stripped-down band of electric guitar, guitar, bass, and drums. When they played the Iron Horse in Northampton in early January, their unvarnished intensity kept the audience on the edge of its seats and continuously involved with the music. “I love playing houses like the Horse; they can’t seem to get enough of us and we can’t get enough of them,” Buddy exulted. “We’ve got to get that live sound onto a CD; it’s got a very different feel from our studio work.” On stage, Julie’s spiritual songs share the program with acoustic country/roots ballads, alt country rock tunes, and some mainstream (albeit unvarnished) country distillations. The overall effect is to lighten up and energize the show as a whole, making serious Julie Miller songs like Broken Things all the more welcome in their contrast. Ms. Miller’s patented wacky stage patter-which frequently explores the highways and byways of the Millers’ 20+-year marriage/musical partnership--is another buoyant influence. (Spirituality without humor is a long day in church.) During their January Iron Horse engagement, Buddy, who usually lets his guitars do the talking, stole the show with insights of his own. When a cat fancier in the audience asked Julie about Pee-Wee, one of the Millers’ multitude of cats and a prominent presence on the couple’s web site, Buddy’s response was Pavlovan: “We don’t talk about PeeWee in concert,” he interjected. . . . All those cats; ten litter boxes. I live just for the few minutes that I can get away on stage,” said he, transporting the Iron Horse and its predominantly boomer audience to the Borscht Belt. With cat queries in the rear view mirror, one

final, more serious, question remains: How have audiences reacted to Rachel?

“We haven’t performed it yet,” confessed Julie Miller. “When

the time is right, we will find a way to do it justice before a

live audience.” Until then, take my recommendation to heart: Buy the

disk, jump directly to track ten, and unfasten your spiritual

seat belt. |

ter

-- that move inexorably forward

with evangelical authority. Their spontaneity and clarity of purpose

are the spiritual equal of Julie’s lyrics. (It’s also a great,

distinctly American take on sacred music.) After that, the voices

reenter, repeating and affirming the responding chorus. The organic

sequencing of those three choruses -- vocal-instrumental-vocal -- has a

call-response-response to the response quality that pushes the music beyond the

stratosphere.

ter

-- that move inexorably forward

with evangelical authority. Their spontaneity and clarity of purpose

are the spiritual equal of Julie’s lyrics. (It’s also a great,

distinctly American take on sacred music.) After that, the voices

reenter, repeating and affirming the responding chorus. The organic

sequencing of those three choruses -- vocal-instrumental-vocal -- has a

call-response-response to the response quality that pushes the music beyond the

stratosphere.