|

Music Review by Lou Wigdor The Opera Is a Dream? |

What

greater dread for a composer than never to hear his music performed?

That was Beethoven’s fate from age fifty, when he became stone deaf.

The late string quartets, the final piano sonatas, the ninth symphony,

and the heaven-storming Missa Solemnis-Beethoven heard them all in his

head but never in the sensate world. What

greater dread for a composer than never to hear his music performed?

That was Beethoven’s fate from age fifty, when he became stone deaf.

The late string quartets, the final piano sonatas, the ninth symphony,

and the heaven-storming Missa Solemnis-Beethoven heard them all in his

head but never in the sensate world.

Sixty-one-year-old Pulitzer Prize winning composer Lewis Spratlan has perfect hearing, but has gained deeper empathy with Beethoven’s predicament. In April of 2000, Spratlan, who has been on the music faculty of Amherst College since 1970, received the Pulitzer Prize in music for a concert version of the second act of his three-act opera, Life Is a Dream. “Winning the Pulitzer was exhilarating; so was hearing and seeing the opera’s second act performed for the first time in its then twenty-two year existence. Perhaps one day, I‘ll get to hear the first and third acts as well,” muses Spratlan, who will hear the opera’s Pulitzer-winning segment for only the third time, this May 7th in its unstaged New York debut with the New York City Opera’s Showcase of American Composers series. “Of course I know what Acts I and III sound like, but never having heard them performed leaves me with a decisively incomplete picture,” he continues. “I have an internalized, idealized sense of the music, but I’m missing the physicality of the sound. That brings-for lack of a better term-a luminosity to the music. Even more critical is the unknowable leap that the performers-even if you know who they are and can image how they might sound-bring to your work. Last October, the great soprano, Lucy Shelton, premiered my work, Of Time and the Seasons, a cycle of seven songs set to Finnish texts. Lucy’s performance added exponentially to the music. There was no way that I could have conceived of that leap.” Bringing the opera’s second act

into the sensory world was anything but a walk in the park. Originally

commissioned by the defunct New Haven Opera Theatre in 1975, the opus

debuted on paper in 1978-just in time for the Theatre’s dissolution.

Dejected but h Two weeks after the announcement,

Gunther Schuller, the chairman of the award committee, told The New

Yorker why Spraltan’s opus was special. “Not only is this the

first opera in nearly forty years to receive a Pulitzer, but I can’t

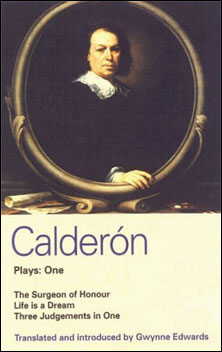

remember when a Pulitzer Life Is a Dream is

based on the seventeenth-century play, La Vida Es Sueño, by

the great Spanish dramatist, Pedro Calderón. In the libretto, crafted

by James Maraniss, Basilio, an aging king, imprisons his son,

Segismundo, in a tower from birth, fearing astrological predictions

that he will become a violent and tyrannical ruler. At the end of

Act I, “Calderón’s vision questions the status of everything in sight-personal values, roles, self-identity; relationships; consciousness; even life itself,” observes Spratlan. “At the work’s end, the Catholic Calderón found social stability where Jim and I found a hollowing out of the spirit beneath the wheel of social convention. But that in no way diminishes Calderón’s dramatic examination of relativism and the competing forces of natural impulses versus the social order.” Adds Maraniss, “The notion of life as a dream is archetypal. Who knows where it started. . . with the Sumerians? Calderón certainly worked that archetype with extraordinary insight and passion. Every few years, the 400-year-old play gets performed in Boston or New York. That’s what I call staying power.” When Spratlan got word of the jury’s decision, he was floored. “Seeing my name in the national press, being honored at the awards ceremony, and receiving congratulations from everyone and his sister were more than a bit seductive. This was the breakthrough that I or any other American composer would beg, steal, or borrow for. With the clout of the Pulitzer, I expected the commissions to fly in. Well, my phone has rung more than it used to; I’ve gotten some genuinely exciting commissions, but nada for a performance of the opera itself, which I consider my masterwork. I still haven’t heard the damn thing and I’m heart sick.” Shortly after winning the Pulitzer, Spratlan , and his publisher, G. Schirmer, Inc. and Associated Music Publishers, Inc., sent a tape of Act II and a score and libretto of the entire opera to a broad brush of potentially receptive American opera houses. “They proved their risk averseness,” explains Spratlan. “I understand that staging a new opera involves a substantial capital investment and financial risk, but there must be some mechanism in this country to bring an opera and its Pulitzer-winning segment to the public,” Spratlan remarks. “Had I been French, Finnish, or a citizen of any number of other European countries, I’m pretty sure that having received a Pulitzer-level honor, my opera would have already been performed and you wouldn’t be writing this article.” In the extreme, some of Spratlan’s rejections embodied the spirit of burocrazia buffo. “One of them came with a check list of little boxes,” Spratlan told the web zine, New Music Box, in its June 2000 issue. “It read, Thank you very much, Mr. Spratlan. Please take note of the reasons that we did not accept your piece. You know, 1,3,5,7,9,10,11, 12 and 14 were all checked,” Spratlan affirmed. “Do not overestimate the intelligence of your audience was one of the things. [So was] Include reprises. Still another advised, Melody! Melody! Melody!” If melody rules, then blame Life Is A Dream’s inspired atonality as the likely cause of the opera companies’ collective timidity. That’s a travesty, because Spratlan’s frequently mercurial, nonstop inventive music in Act II seamlessly complements librettist Maraniss’ buoyant, unstuffy prose. The marriage consistently and successfully imparts the spirit of Calderón, which is to say that the opera is itself great literature. To that end, Spratlan wields a dazzling palette, as well as frequent shifts in tempo, rhythm, and dynamics to capture Segismundo’s own shifting impressions, temperament, and states of consciousness. The chameleon-like score repeatedly reinvents itself in depicting resonant characters and new action in the story line. Spratlan paints Segismundo’s saturnine father, Basilio, in constricting twelve-tone terms. He gives Segismundo more musically unfettered treatment, which complements his rapid-fire impressions and experiences. And the strikingly beautiful passacaglia toward the end of the act is all the more poignant in its avoidance of tonal resolution. The times have never been more promising for operas composed by Americans, observes Kip Cranna, Music Administrator at the San Francisco Opera. “In the last ten years, American operas have begun to come into their own,” he emphasizes. “As a group they have earned a separate identity, a discernable profile. We used to talk about the Great American Novel; now it’s the Great American Opera. And it’s not just Adams and Glass. There’s tremendous activity accompanied by growing public demand.” The industry trade group, Opera America, keeps a running list of 130 American operas, he notes. It also maintains a list of about 200 operas in progress. In the not-too-distant future that second list will welcome a new chamber opera by Spratlan, commissioned by the San Francisco Opera for April of 2004. But as Cranna admits: “The repertoire that people are coming to hear is slightly more conservative than Life Is a Dream.” The costs of those productions can be staggering, he continues. Underwriting a new production’s visuals—the non-musical aspect of the opera-can alone run anywhere from $100,000 to half a million dollars. “We often partner with other opera houses to share those expenses and materials like scenery and costumes,” he notes. “This business is like few others: if you commission a work yourself, you ultimately don’t own it. You do reap some of the glory though, if it’s successful. Another plus is that it’s a lot easier to raise money from foundations and individual donors for new American works than for new productions of Madame Butterfly. And singers and musicians rarely hesitate to learn new roles and material. It’s important to them as creative artists.” And what about the audience itself? “Our top ticket price is around $155. That’s $300 a couple. When you figure in parking and dinner, you’re looking at an expensive evening. If a couple isn’t sure about an opera, there’s a strong temptation to stay home and watch Friends. “Life Is a Dream Act II will see a May 7 unstaged performance in the New York City Opera’s Showcase of American Composers series,” notes Norman Ryan, Spratlan’s manager with G. Schirmer. “We expect to wake up a lot of ears at that performance. The Showcase series is attended by industry insiders in search of new programming. This is a big step for us. News travels fast by word of mouth in the close-knit opera community. An enthusiastic response will spread swiftly, especially among the growing number of companies that are embracing new American operas.” Ryan is also segmenting the market regionally to target Spanish speaking populations. “La Vida Es Sueño is one of the supreme accomplishments of Spanish literature. Southern Florida, Spain, and other areas with strong Spanish cultural roots all have a cultural affinity with Lew’s opera.” Still, a complete performance remains elusive after twenty-four years. “The Pulitzer award and those great accounts of Act II really got my hopes up,” Spratlan admits. “But until its full realization, the opera will inhabit a sort of twilight world, a musical limbo. Until its performance as a cohesive work, Life Is a Dream will remain just that—a dream.” |

opeful,

the 37-year-old Spratlan and his publisher sent the score to a host of

opera companies-all without success. Life Is a Dream remained

unheard by Spratlan or anyone else until the year 2000, when the

composer spun off the opera’s second act for two concert-version

performances, the first at Amherst College in January and the second

at Harvard University two months later. Spratlan sent a tape of the

second performance to the Pulitzer Prize jury at Columbia University

along with his nomination papers (“I nominated myself; it’s

customary for composers to routinely nominate large works for the

Pulitzer,” he notes). In April, Spratlan got the earth-shaking news:

the Pulitzer jury had chosen Life Is a Dream-Act II Concert Version

as the first segment of a complete opera to win America’s most

prestigious honor in music.

opeful,

the 37-year-old Spratlan and his publisher sent the score to a host of

opera companies-all without success. Life Is a Dream remained

unheard by Spratlan or anyone else until the year 2000, when the

composer spun off the opera’s second act for two concert-version

performances, the first at Amherst College in January and the second

at Harvard University two months later. Spratlan sent a tape of the

second performance to the Pulitzer Prize jury at Columbia University

along with his nomination papers (“I nominated myself; it’s

customary for composers to routinely nominate large works for the

Pulitzer,” he notes). In April, Spratlan got the earth-shaking news:

the Pulitzer jury had chosen Life Is a Dream-Act II Concert Version

as the first segment of a complete opera to win America’s most

prestigious honor in music. committee

was so transfixed. Usually, we listen to the first five or ten minutes

of a submission and then skip to the end. Spratlan’s work lasted an

hour, and nobody wanted it to stop,” he emphasized. Schuller’s

praise extended to the performance. Under the baton of Spratlan’s

former student, J. David Jackson, a thirty-four piece ensemble and a

cast of splendid singers, including the Met’s John Cheek and the

rising young tenor and soprano, Alan Glassman and Christina Bouras,

gave a riveting performance that made an irrefutable case for Act

II. “It was just impeccable, and I think I’ve used that word

only four times in my life,” Schuller told The New

Yorker.

committee

was so transfixed. Usually, we listen to the first five or ten minutes

of a submission and then skip to the end. Spratlan’s work lasted an

hour, and nobody wanted it to stop,” he emphasized. Schuller’s

praise extended to the performance. Under the baton of Spratlan’s

former student, J. David Jackson, a thirty-four piece ensemble and a

cast of splendid singers, including the Met’s John Cheek and the

rising young tenor and soprano, Alan Glassman and Christina Bouras,

gave a riveting performance that made an irrefutable case for Act

II. “It was just impeccable, and I think I’ve used that word

only four times in my life,” Schuller told The New

Yorker. Basilio

has second thoughts and orders Segismundo, now a young adult, drugged

and brought to the court for evaluation. Act II opens at court, with

Segismundo awakening to a quasi-hallucinatory sequence of sensual

pleasures, explanations from his attendant, scolding servants,

conniving cousins, admonishments from his father, and murder. By the

end of Act II, he has flunked his father’s test, is subdued, drugged

and returned to the tower. When Segismundo awakens in Act III from his

stupor, he begins to doubt his ability to grasp reality itself. Were

his memories of court real or a dream?

Basilio

has second thoughts and orders Segismundo, now a young adult, drugged

and brought to the court for evaluation. Act II opens at court, with

Segismundo awakening to a quasi-hallucinatory sequence of sensual

pleasures, explanations from his attendant, scolding servants,

conniving cousins, admonishments from his father, and murder. By the

end of Act II, he has flunked his father’s test, is subdued, drugged

and returned to the tower. When Segismundo awakens in Act III from his

stupor, he begins to doubt his ability to grasp reality itself. Were

his memories of court real or a dream?