“In

the singer-songwriter world, performers just naturally write about

themselves. It’s expected. It’s the coin of the realm,” remarked

one of that world’s most gifted practitioners, Richard Shindell.

Apart from an occasional musing about his own romantic life (typically

in the second person, e.g., You Again), Shindell has

consistently focused his energies outward—notably

on a varied cast of characters that he creates and inhabits from a

first-person-singular point of view. These characters live and breathe

with vitality in Shindell’s latest album, Courier (Signature

Sounds), a live concert recording that collects some of the more

memorable portraits from his first four albums.*

(The album also includes other Shindell stand-bys like Are

You happy Now? and Transit as well as covers by Lowell

George and Shindell’s fellow Jerseyite Bruce Springsteen.) “In

the singer-songwriter world, performers just naturally write about

themselves. It’s expected. It’s the coin of the realm,” remarked

one of that world’s most gifted practitioners, Richard Shindell.

Apart from an occasional musing about his own romantic life (typically

in the second person, e.g., You Again), Shindell has

consistently focused his energies outward—notably

on a varied cast of characters that he creates and inhabits from a

first-person-singular point of view. These characters live and breathe

with vitality in Shindell’s latest album, Courier (Signature

Sounds), a live concert recording that collects some of the more

memorable portraits from his first four albums.*

(The album also includes other Shindell stand-bys like Are

You happy Now? and Transit as well as covers by Lowell

George and Shindell’s fellow Jerseyite Bruce Springsteen.)

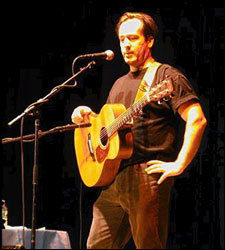

In Courier, Shindell

transforms himself into a military courier, a truck driver, a Civil

War widow, an immigration officer and his charge (a Latino fisherman),

a Civil War recruit, and the venerable Mary Magdalen. “In

performance, I’m not acting; what I do is more like an author

reading a short story, but with the added influence of the music and

its cadences,” Shindell explained in an interview last March. “It’s

more like I just imagine the character, the setting, and the story.

And it’s only for three or four minutes. I get in and get out

quickly. There’s an economy to the whole thing.”

That economy reveals Shindell as an

artist of uncommon intuitive gifts, whose verbal brush strokes

strategically conjure up more with less. In Reunion Hill (track

# 7 on Courier), his masterful lament for Joan Baez, Shindell

recalls the pain of personal loss in war not by chewing the scenery or

overpainting it, but by evoking associations with unremarkable objects

and actions. His Civil War widow, ten years later, remembers that

ragged army that limped across these fields of mine—not through a

macabre body count, but through the everyday objects that the soldiers

left behind:

Even now I find their things

Glasses, Coins, and Golden Rings

And she reflects on the loss of her

husband not through the particulars of her suffering or the

deprivations of war, but through her evanescent last glimpse of the

man as he walks across the valley and disappears into the trees.

Shindell’s songs impart visual

impressions and additional storyline evidence in support of moral

subtexts that lie just below the surface. He never polemicizes though,

instead allowing his listeners to draw their own inferences (even

though those conclusions are pretty much set-ups). That engages them

in more active involvement with the song, adding greater moral force

and emotional resonance to Shindell’s message and the listening

experience.

On the sur face,

Shindell bears little resemblance to his characters, but if you take

the time, you’ll likely detect at least an isthmus of common ground.

“There’s almost always a connection,” he insisted. Reflecting on

the road-weary truck driver in Courier’s second track, The

Next Best Western, Shindell confessed, “I’ve never driven or

even set foot in a truck, but I do spend a great deal of time on the

road far away from my home and family.”** So Shindell can sing with

more than token empathy for his exhausted teamster, who in the middle

of the night craves deliverance not via the preacher breathing fire

from his dashboard but at the next station of the hospitality

industry. face,

Shindell bears little resemblance to his characters, but if you take

the time, you’ll likely detect at least an isthmus of common ground.

“There’s almost always a connection,” he insisted. Reflecting on

the road-weary truck driver in Courier’s second track, The

Next Best Western, Shindell confessed, “I’ve never driven or

even set foot in a truck, but I do spend a great deal of time on the

road far away from my home and family.”** So Shindell can sing with

more than token empathy for his exhausted teamster, who in the middle

of the night craves deliverance not via the preacher breathing fire

from his dashboard but at the next station of the hospitality

industry.

Like many of Shindell’s songs, Next

Best Western teems with religious language and imagery that

reflects its author’s seminarian past. (He attended Union

Theological Seminary in Manhattan.) Hence, the truck driver’s

prayer: Show a little mercy for this weary sinner and deliver me to

. . . we all by now know where. In The Ballad of Mary Magdalen (track

# 12) we learn that Mary made the enlightened choice because it was

His career or mine. And in what has become a coda at Shindell’s

concerts (Courier included), the song-tale Transit

chronicles an unwitting secular pilgrimage of irate rush hour

motorists down the New Jersey Turnpike and into the cleansing waters

of the Delaware Water Gap.

On occasion, Shindell digs deep into

eschatological terrain. Beyond the Iron Gate on his Reunion

Hill album is ostensibly about an elderly man who leaves the

grounds of his rest home and experiences an epiphany upon busting

loose. But the song works on a deeper level. When I asked Shindell

whether getting beyond the iron gate wasn’t about transcending the

limits imposed by the ego, his reply was even terser than his writing:

“The song is about death,” he responded with solemnity. But it’s

also, I suspect, about Shindell’s own faith, presumably informed by

some degree of metaphysical insight:

But it was easy slipping through

As easy as the morning dew . . .

I held on to all my might

Held on to a world made right

Back inside the iron gate, I was

determined to resolve a secular puzzlement of my own about an

uncharacteristic Shindell song. Waiting for the Storm on

his Somewhere Near Patterson disc threw me because of its

incongruity with the rest of Shindell’s work. It’s a sketch about

a working class Floridian who, anticipating a big-time hurricane,

sends his wife and kids to safety, sets his furniture out in the yard,

and hunkers down in his rocking chair.

I’ve made my preparations

There’s nothing left to do

Except sitting in this rocking chair

Waiting for the storm

What’s different about this song

from the others? The music fits half the situation and contradicts the

other half. Propelled by Larry Campbell’s virtuoso mandolin playing,

the tune sports an up-tempo, whistle-while-you-work vitality. The guy’s

taken care of business, he’s made his preparations, but guess what—this deeply troubled redneck’s children may soon be fatherless.

If you find such contradictory juxtapositions intriguing, you might

take intellectual pleasure in Waiting for the Storm. But

for Shindell, the song is uncharacteristic, because he never

intentionally trades his moral compass for intellectual conceits. In

that, he is much like his hero, Tom Waits, who almost always manages

to treat his characters (and they are a colorful lot) with at least a

kernel of respect. So here, according to Shindell, is how the song

took shape: “Initially, it was supposed to be about a macho guy in

Florida whose response to a hurricane was to tough it out by staying

put in the path of the storm. Along the way, I got bored with him and

did what I could to make him more vulnerable. The character turned

into a hybrid.”

One last item on the agenda.

Conspicuously absent from Courier (with the exception of one

track) is the energizing musical presence of multi-instrumentalist

Larry Campbell. For the last half decade, Campbell has been nothing

less than Shindell’s musical alter ego. (He has recently devoted

more and more of his energies to the Bob Dylan band.) Together,

Shindell and Campbell have produced one strong album, Somewhere

Near Patterson, and one indispensable one, Reunion Hill.

They have also served up some thrilling concerts that have gained

national press attention. Not only is Campbell a masterful arranger

and gifted improviser on a ton of instruments—violin, mandolin,

bouzouki, and electric, acoustic and pedal steel guitars—he is a

startlingly inventive composer of instrumental passages that

complement and energize Shindell’s songs. Campbell’s concise sonic

statements share the laconic spirit of Shindell’s words. And their

musical buoyancy adds just the right kinetic gloss to Shindell’s

predominantly serious themes. It would be tragic, especially for

Shindell’s future recordings, if the two were to go separate ways,

but it should be Shindell’s end of the bargain to inspire Campbell

more regularly with new material that only Richard Shindell can

write.

|