Hearing

Hungary’s leading folk chanteuse, Márta Sebestyén, on disc is a good

thing. But it is no substitute for the real thing. I own seven or

eight of her discs, (most with Hungary’s premier folk group, Muzsikás), and recommend them all. But none of them quite captures the

unique, commanding, physicality of her unmiked voice in an intimate

gathering. This I learned last February at The Folk Roots of the

Music of Béla Bartók, a lecture-demonstration by Muzsikás at the

New England Conservatory, in Boston. At 4 in the afternoon, in the

company of about forty others, I found myself front row center in a

parquet-floored room with neoclassical moldings and a thirty-five foot

ceiling. Out sauntered the five informally garbed, middle-age

Hungarians, with lead violinist Mihály Sipos on the far left followed

by Dániel Hamar on bass, Péter Éri on viola, and László Porteleki on

second fiddle. On their heels emerged the diminutive Ms. Sebestyén,

who positioned herself in the center of the group, about eight feet in

front of me. Hearing

Hungary’s leading folk chanteuse, Márta Sebestyén, on disc is a good

thing. But it is no substitute for the real thing. I own seven or

eight of her discs, (most with Hungary’s premier folk group, Muzsikás), and recommend them all. But none of them quite captures the

unique, commanding, physicality of her unmiked voice in an intimate

gathering. This I learned last February at The Folk Roots of the

Music of Béla Bartók, a lecture-demonstration by Muzsikás at the

New England Conservatory, in Boston. At 4 in the afternoon, in the

company of about forty others, I found myself front row center in a

parquet-floored room with neoclassical moldings and a thirty-five foot

ceiling. Out sauntered the five informally garbed, middle-age

Hungarians, with lead violinist Mihály Sipos on the far left followed

by Dániel Hamar on bass, Péter Éri on viola, and László Porteleki on

second fiddle. On their heels emerged the diminutive Ms. Sebestyén,

who positioned herself in the center of the group, about eight feet in

front of me.

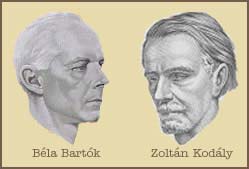

Dániel Harmar, who did most of the

talking during the two-hour demonstration, explained that shortly

after the turn of the 20th century, a young Béla Bartók (

1881-1945) and his colleague and close personal friend, Zoltán Kodály

(1882-1967),

had helped launch modern ethnomusicology in Hungary. Their mission: to

collect, transcribe, analyze, and propagate Hungary’s living folk music* while

the getting was still good. The two divided the job geographically,

with Kodály beginning in the northeast and Bartók in the southwest. Muzsikás, continued Harmar, would in the next two hours perform

material from regions that Bartók had visited, including some music

that the composer had collected himself. But the group was no less

indebted to Kodály. Today, thanks to both composers’ pioneering

work, Muzsikás and other performers and scholars can draw on more than

200,000 field recordings, Harmar noted with gratitude. (1882-1967),

had helped launch modern ethnomusicology in Hungary. Their mission: to

collect, transcribe, analyze, and propagate Hungary’s living folk music* while

the getting was still good. The two divided the job geographically,

with Kodály beginning in the northeast and Bartók in the southwest. Muzsikás, continued Harmar, would in the next two hours perform

material from regions that Bartók had visited, including some music

that the composer had collected himself. But the group was no less

indebted to Kodály. Today, thanks to both composers’ pioneering

work, Muzsikás and other performers and scholars can draw on more than

200,000 field recordings, Harmar noted with gratitude.

Following that prelude, Harmar picked

up his bass, and joined by the violins and viola, bowed up a

medium-tempo dance--a caradas-that had been collected by Bartók

in southern Transylvania (which had belonged to Hungary before the

Great War). Then Ms. Sebestyén demonstrated her vocal authority.

Emanating predominantly from her throat center, her laser-like voice

parted the sea of semi-sweet strings, etching out the song’s leading

edge of bitter-sweet emotionality. For its next offering, the

ensemble, this time without Ms. Sebestyén and deploying a three-foot

vertically held wooden long-flute, launched into a brisk dance that

pushed against the outer limits of pitch and rhythm, and built to a

furious tempo. Under other circumstances, dancing would have been

irresistible.

“We were all born in Budapest,”

noted Harmar. “I studied classical piano for 18 years and classical

bass for six. I learned to play in a style dominated by German ideas

of classical precision and intonation. I had relatives who lived in

the villages, but I never heard actual village music until I was

twenty,” he confessed. Instead, Harmar like many Hungarian urbanites

shared the misconception of Hungarian folk music as either packaged

performances by state-run ensembles or polished restaurant fare in the

hands of virtuosic Gypsies. Not so Péter Éri and Márta Sebestyén. Eri’s

father was a Kodály colleague, who did fieldwork with the composer. Sebestyén’s first contact with the music, she insists, was prenatal.

“My mother was a student of Kodály. I truly believe that I absorbed

the music when she was pregnant with me in his classes,” she mused.

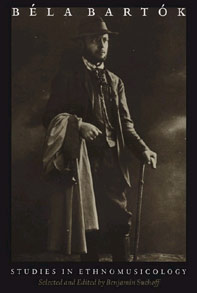

Béla Bartók’s first exposure was

closer to Harmar’s experience. A classical music prodigy in both

piano and composition, Bartók grew up in several towns** in eastern

and northern Hungary, as close as six miles from traditional villages.

“But he didn’t know this music at all,” observed Harmar.  That

changed dramatically in 1903 when at age 22 Bartók discovered the real

thing, sung by a talented maid at the country estate managed by his

brother-in-law. Before

that, Bartók had embraced the commonly held myth that credited Gypsies

as the true progenitors of Hungarian music. (Hungarian village

musicians were thought to have learned (and corrupted) everything they

knew from the Gypsies.) In 1905, the young pianist/composer met and

joined forces with Kodály, then on the threshold of receiving his

doctorate from the University of Budapest for a thesis on the stanzaic

structure of Hungarian folk songs. Armed with a Edison phonograph, Bartók

went

into the field in 1906, visiting Slovakian villages (Slovakia was then

part of Hungary.) Subsequent fieldwork brought him to Transylvania in

1907 and Romania in 1909. In 1912, he sought out Ruthenian, Serbian,

and Bulgarian melodies at their source, and even visited Northern

Africa in 1913, where he recorded about 200 Arabic melodies. By and

large, the end of the Great War marked the end of Bartók’s field

work (Kodály, in contrast, kept at it for decades). But Bartók continued to write books and articles that analyzed the folk songs of

Hungary and its neighbors structurally, morphologically and

comparatively. (Bartók was emphatic in attributing the origins of

Hungarian music to a non-European pentatonic scale and tracing the

Magyars’ ancestral origins to the Volga River basin.) That

changed dramatically in 1903 when at age 22 Bartók discovered the real

thing, sung by a talented maid at the country estate managed by his

brother-in-law. Before

that, Bartók had embraced the commonly held myth that credited Gypsies

as the true progenitors of Hungarian music. (Hungarian village

musicians were thought to have learned (and corrupted) everything they

knew from the Gypsies.) In 1905, the young pianist/composer met and

joined forces with Kodály, then on the threshold of receiving his

doctorate from the University of Budapest for a thesis on the stanzaic

structure of Hungarian folk songs. Armed with a Edison phonograph, Bartók

went

into the field in 1906, visiting Slovakian villages (Slovakia was then

part of Hungary.) Subsequent fieldwork brought him to Transylvania in

1907 and Romania in 1909. In 1912, he sought out Ruthenian, Serbian,

and Bulgarian melodies at their source, and even visited Northern

Africa in 1913, where he recorded about 200 Arabic melodies. By and

large, the end of the Great War marked the end of Bartók’s field

work (Kodály, in contrast, kept at it for decades). But Bartók continued to write books and articles that analyzed the folk songs of

Hungary and its neighbors structurally, morphologically and

comparatively. (Bartók was emphatic in attributing the origins of

Hungarian music to a non-European pentatonic scale and tracing the

Magyars’ ancestral origins to the Volga River basin.)

Hungarian folk music was grist and

inspiration for Bartók’s own compositions, but it was just as much

an end unto itself-a “precious spiritual treasure,” he insisted.

Listening to Márta Sebestyén and Muzsikás reveals why. In their hands,

the music always conveys a mixed emotionality. It is rarely

unilaterally sweet, or despondent, or bitter, but ranges along terrain

from sweet-and-sour to bitter-sweet. Nearly every song, regardless of

its lyrics, imparts a mixed emotional message-an echo, if you will, of

life’s joys and aspirations holding hands with life’s inescapable

disappointments and limitations. To convey that effect, Muzsikás and

other practitioners employ a variety of  devices:

slightly sharped, wavering intonation; marginally unsettling melodic

interval leaps; unexpected syncopations;

accelerating tempos; and resinous, vinegary timbres. devices:

slightly sharped, wavering intonation; marginally unsettling melodic

interval leaps; unexpected syncopations;

accelerating tempos; and resinous, vinegary timbres.

“The Hungarian source is nearest to

me and therefore the strongest,” Bartók wrote to a Romanian

folklorist in 1931. That is evident throughout his 40+ years as one of

the 20th century’s great composers. Bartók’s compositions include

avowedly idiomatic works like the violin duos and the Mikrocosmos piano

studies, that preserve the structural integrity of peasant melodies

while recasting them in expanded 20th century harmonic and chromatic

language. There are creations like the 4th quartet and the final

movements of the fifth and sixth quartets that deconstruct and

reconstruct folk themes in consistently surprising ways. And there are

late-period commissioned pieces like the Concerto for Orchestra and

the Violin Concerto that, while lacking sustained folk melodies

per se, still retain melodic, rhythmic, and coloristic nuances

informed by the Hungarian cultural-spiritual heritage.

Bartók repeatedly railed against the

repackaging of Hungarian village music by Gypsies for consumption by

bourgeois urbanites. His own music as well has received more than its

share of tampering in the urban elitist market -not by Gypsies but by

classical music interpreters. As in so many earthly endeavors, there

are multiple ways to skin a cat. One is to give the music a

waxed-fruit gloss and to pump up anything suggesting nativistic

mannerisms. I remember leaving the Kennedy Center reeling one night

twenty-five years ago after hearing Hungarian expatriate Eugene

Ormandy and his Philadelphia forces treat Bartók’s Divertimento

for Orchestra to--the Philadelphia Cream Cheese Sound. A

very different strategy is to imbue the music with vampirizing

precision, by obsessing on the score while neglecting the music’s

roots and soul. That isn’t to say that classical musicians should

play like Hungarian peasants, but why not at least strive to find a

stillpoint where the music can breathe on its own terms? For a

recorded performance that gets it right, I recommend a new cd of Bartók’s 44 violin duos (ECM) by violinists András Keller and

János Pilz of Hungary’s Keller Quartet. Their restraint, finesse,

and technical mastery consistently allow the music to resonate on its

own spiritual terms.

Ms. Sebestyén and Muzsikás cut their

folk music teeth in Hungary’s Táncház movement of the 1970s.

Taking its name from the traditional village dancehouse, it brought

the roots music of the villages to Budapest and other cities and

blossomed as a borderline subversive alternative to “official”

state-run folkloric ensembles. The Táncház movement combined several

key attributes: audiences dominated by urban professionals attended

events to dance as well as listen; and scholars and performers

traveled to the villages to learn the music and instruments at their

source (including at times precarious jaunts over the Transylvanian

border into Ceaucescu’s Romania.) Harmer, for one, learned the

virtues of playing a short-bowed three-string bass. “How did I

learn? A villager just moved my hands holding the instrument and bow,”

he explained. The shorter bow strokes become increasingly merciful, he

noted, when you’ve been playing a wedding party that begins on

Sunday afternoon and runs late into Monday morning.

Ms. Sebestyén also sought out

instruction at its source. Vocal music, she explained, is considered

more demanding, more nuanced, than its instrumental counterpart. “Early

on, I visited ladies in the villages, who sang with great intimacy,”

she recalled. “When I asked them, Would you sing for me?,

they repeatedly turned me down. Once I asked this old guy, who

responded: “Why the hell should I sing for you; I’m not in the

mood. I don’t have anything to drink.” Ms. Sebestyén’s

persistence and passion paid off. She absorbed the styles and spirit

of the best singers of the day. And she met an elderly woman from

Moldavia, whose singing twenty-five years earlier had moved Ms. Sebestyén

so profoundly that she has honored that voice in her own

singing ever since. “I had to wait twenty-five years to meet her.

When I did, I confessed secretly that she was my master,” revealed Sebestyén. But this humblest of folk divas remains grateful to all the

villagers who have helped shape her art. “Whenever I sing, they’re

in my mind. They helped me to understand that folk music has an

instant power and beauty that is beyond language.”

“At village wedding parties, the

fiddler was crucial,” noted Harmar. “He knew every villager’s

favorite melody and he made sure that everyone got his due. At the

same time, the musicians always improvised. It was the tradition.”

Improvisation was in deft hands during the two-hour demonstration,

particularly in the nimble fingers of lead violinist, Mihály Sipos,

who played with passion and inventiveness, at times leading the others

into increasingly accelerated tempos.

In their repertoire, Muzsikás shadowed

Bartók the ethnologist on some of his more intriguing stops.

From the East Carpathians, Sipos and Harmar performed a slow,

percussive dance melody propelled by Harmar’s regular bow-slaps on

the gardon, a four- stringed (all tuned to d below middle c)

medieval member of the cello family that resonated like a drum. And

the Hungarians played a dance from Romania’s Marmaros region, once

home to an indigenous Jewish culture, visited and honored by Bartók in

one of his 44 violin duos. “When we tried to do our own collecting

in the Marmaros region, we came up empty handed. Everyone had been

murdered in the Holocaust,” Harmar lamented. “What music we

learned of the Marmaros was all second-hand from Gypsies.” Earlier,

Muzikas had played one of Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances, which the

composer had distilled for piano and his collaborator, Zoltán

Szckely, had arranged for violin

and piano. Recalling Bartók’s own

recorded performance of some of the dances with violinist Joseph Szigetti,

Harmer commented, “You could tell from his piano passage that Bartók

was hearing the flute. We will play the dance as Bartók would have

heard it in the field.”

performance of some of the dances with violinist Joseph Szigetti,

Harmer commented, “You could tell from his piano passage that Bartók

was hearing the flute. We will play the dance as Bartók would have

heard it in the field.”

Ms. Sebestyén’s final offering-a

plaintive shepherd song-underscored Bartók’s spiritual attribution

of the music. Singing a cappella, she conveyed a lilting melody that

wore innocence and vulnerability on its sleeve. Woven into the song’s

fabric was a wistful sadness that seemed to reflect the limitations of

the human life cycle itself. Then, with her singing done, she reached

for a two-hole Moldavian flute, and offered up a delicate coda that

perfectly mirrored the vulnerability and restraint of its vocal

predecessor. It was all transparency of ego and genuineness of soul-a

memorable lesson at the New England Conservatory that afternoon.

|