|

Music Review by Lou Wigdor Chasin’

the Suite |

There’s never been a better opportunity than the

present to deepen your appreciation of John Coltrane’s towering

masterpiece, A Love Supreme. Last fall saw the simultaneous

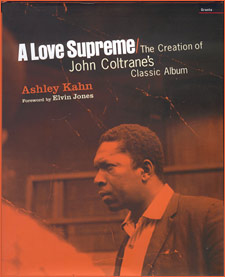

release of two milestones central to the subject. Ashley Kahn’s

perceptive, meticulously researched A Love Supreme: The Story of

John Coltrane’s Signature Album (Viking) is surely the definitive

account of the work’s gestation and influence. Verve Music Group’s

release on its Impulse label of the two-CD A Love Supreme: The

Deluxe Edition presents the original 33-minute recording in

sparkling sonics and adds fascinating out-takes, including two

scrapped sextet versions of the opening movement, augmenting the

“classic quartet” of McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones, Jimmy Garrison, and

Trane with Archie Shepp and bassist, Art Davis. The Deluxe Edition

also dishes out a recording—long available in Europe—of the

suite’s only complete live performance, recorded at the Antibes Jazz

Festival eight months after the studio version. The new book and CD

set are what economists would call complementary goods, marketers

would term a great tie-in, and music lovers must regard as a blessing. There’s never been a better opportunity than the

present to deepen your appreciation of John Coltrane’s towering

masterpiece, A Love Supreme. Last fall saw the simultaneous

release of two milestones central to the subject. Ashley Kahn’s

perceptive, meticulously researched A Love Supreme: The Story of

John Coltrane’s Signature Album (Viking) is surely the definitive

account of the work’s gestation and influence. Verve Music Group’s

release on its Impulse label of the two-CD A Love Supreme: The

Deluxe Edition presents the original 33-minute recording in

sparkling sonics and adds fascinating out-takes, including two

scrapped sextet versions of the opening movement, augmenting the

“classic quartet” of McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones, Jimmy Garrison, and

Trane with Archie Shepp and bassist, Art Davis. The Deluxe Edition

also dishes out a recording—long available in Europe—of the

suite’s only complete live performance, recorded at the Antibes Jazz

Festival eight months after the studio version. The new book and CD

set are what economists would call complementary goods, marketers

would term a great tie-in, and music lovers must regard as a blessing.

If you enjoyed Ashley Kahn’s previous book,

Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Commonalities in style and format aside, the

books reveal one striking contrast: Davis and Coltrane were utterly

different people. Miles was a musical giant but more than occasionally

abusive to many within spitting range. “You got to make it with

everybody, you know what I mean? You got to fuck the band,” Miles

harangued a distraught Bill Evans, who, as the band’s lone white guy

took more than his share of invective from his sharp-tongued employer.

“Wake up, Paul,” Davis admonished bass virtuoso, Paul

In contrast, the soft-spoken John Coltrane, in the studio for A Love Supreme, was the soul of politeness. “Excuse me,” he intoned after slipping into the wrong key during the suite’s second movement, Resolution. “Excuse me,” he chimed in again when nixing another take of Resolution, whose energy level had dissipated after pianist McCoy Tyner’s entry into a solo. John Coltrane’s politeness was anything but contrived. Hard-wired in a code of conduct that emphasized kindness and respect toward others, Trane’s modus operandi dovetailed with a passionate spiritual commitment to know and serve God through music, contemplation, and daily living. Like many members of the jazz fraternity, the saxophonist had battled alcohol and heroin addiction. In 1957, he jettisoned substance abuse for good and embraced a compact with the Divine that remained his guiding light until—and dare I say, beyond ?—his untimely death from liver cancer in 1967. A Love Supreme, recorded in its entirety on one December night in 1964—the year of the Beatles—stands apart as an enlightened opus of thanks for one man’s spiritual “turnaround” and his ongoing spiritual progress. Released in the US two months later, the suite, by the end of 1965, elevated Trane’s already empyrean reputation. At Down Beat magazine—then the country’s dominant jazz publication—A Love Supreme swept the annual Readers’ Poll for Album of the Year honors. Coltrane himself was a shoe-in as the magazine’s Jazzman of the Year. Anatomy of the suite.

What a remarkable musical accomplishment A

Love Supreme was . . . and remains! Its four sections complement

each other and the whole in perfect balance. The opening movement,

Acknowledgement, begins with a figure that, like a call to prayer,

draws the listener into the movement’s main motif—a passionate

invocation, conveyed and explored from every angle by the tenor

saxophone. For this listener, Coltrane in A Love Supreme

recalls Mahler the symphonist—not so much in the emotions conveyed—but

in the scope and richness of his ascents and descents in both

intensity and pitch and through uncharted, at times enchanted musical

topographies. Near the end of the movement, Trane shifts gears,

introducing the four-note A Love Supreme motif, which he

reiterates in different keys thirty-seven times.

Chant is again prominent in the suite’s fourth and final movement, Psalm. As Kahn observes, the saxophone itself does the chanting—articulating and cantillating the word patterns of Coltrane’s poem of praise and thanksgiving to his Creator. In the recording studio, Jones, on tympani, was unaware that Coltrane was reciting his poem through the tenor saxophone. Regrettably, thousands of listeners over the years have listened to Psalm with the same incomprehension. You’ll view the gentle, meditative final movement in a whole new light when you hear it while reading Trane’s 69-line poem, entitled—Are you surprised?—A Love Supreme. And you’ll also gain greater appreciation for the significance of a note triplet that resurfaces nine times: its parallel phrase is Thank you God! Between the musical pillars of Acknowledgement and Psalm emerge the two inner movements—Resolution and Pursuance. They offer swing-inflected blues-flavored motifs and structures that lend themselves to impassioned modal explorations by the quartet. Resolution builds its intensity on a medium tempo set of traditional changes masked by a marginally angular melody. The movement begins with a lyrical bass introduction from Garrison, which segues into the quartet’s statement of the Pursuance theme. Later, Tyner unleashes a propulsive, inventive piano solo, which he passes like hot musical coals to Coltrane, who takes the intensity to even higher ground. The ascent continues with Pursuance, its faster tempo and concise blues tinted motif an optimal launching pad for improvisations of even greater intensity. Jones sets the stage with a massive drum solo, overflowing with percussive power and polyrhythmic color. Coltrane concisely states the Pursuance theme and hands the wheel over to Tyner. In another brilliant solo, the pianist revs up Pursuance—way up—for Coltrane. With Parkeresque speed, Coltrane launches into an astounding catalog of modal explorations that occasionally swoop down to reclaim swatches of the Pursuance theme. Just as often though, they leave the orbit of their thematic moorings to dance about in creative hyperspace. For intensity and excitement, these moments in Pursuance are A Love Supreme’s high point, both in the studio and in the suite’s 42-minute live performance, recorded eight months later in Antibes. A hybrid musical form. A Love Supreme is decidedly greater than the sum of both its kinetic and contemplative parts. It is a unified masterpiece where everything fits in mood and structure. The movements, their themes, and subthemes resonate with just the right affinity. The tenor saxophone and piano solos are judiciously placed and paced. And the instrumental transitions—virtuosic solos by Garrison and Jones—link the movements with power and grace. For the four-hour, one-evening recording session that yielded the entire original album, Coltrane had thought out the entire suite in advance. Integral to that enterprise was Trane’s construction of spacious windows for improvisatory solo space: “ . . .you could do what you wanted keeping the form in mind. That’s what A Love Supreme was about,” Tyner told Kahn. “To those familiar with classical music, the album’s overall shape suggests aspects of a concerto form, contrasting segments of meter and mood, with moments set aside for soloists,” wrote Kahn. Just as important, there is structural and emotional affinity among the movements that brings an integrated musical personality to the work as a whole. But the similarity ends there. Concerto development dictates absolute scripting of the instruments, both solo and in combination. The exception 100+ years ago was the cadenza, that unbuttoned opportunity for soloists to improvise. But those wild and crazy days are gone, the costs and benefits of improvisational risk taking eliminated by a simple device: you play the cadenza as written, just like any other part of the concerto. In striking contrast, improvisation is a more than an equal partner in A Love Supreme. It reinforces the cohesiveness and thematic development of the whole. And it energizes the suite with spontaneity and controlled unpredictability. A Love Supreme, then, excels as a hybrid musical form that marries improvisation to an integrated structural and thematic plan. Ellington, Mingus, Chico O’Farrell, Sony Rollins, Wynton Marsalis and Carla Bley—all wrote successful suites that accomplished these goals, but did any of them equal A Love Supreme’s cohesiveness and conciseness? Coltrane’s own Meditations, Sun Ship, and his other post-A Love Supreme suites certainly did not. Their components were often brilliantly written and improvised, but the suites themselves rarely exceeded the sum of their parts. It is a mystery, given A Love Supreme’s stunning success, that its form has been infrequently emulated in the thirty-eight years since its release. Is that misfortune yet another consequence of tribalism within both classical and jazz music cultures?—Is the jazz kindred avoiding the task of developing related themes over multi-movement musical forms? Is the classical clan recoiling in hopeless inadequacy over the prospect of improvisation? A singular work not to be repeated? In his final 2 ½ years, Coltrane, when composing in the suite genre, never achieved the musical integrity of A Love Supreme. One possible explanation is that he never allowed himself sufficient time to do so. Kahn observes that Trane stayed away from the studio for an uncharacteristically long six months between A Love Supreme and Crescent, the disc that immediately preceded it. (During his intensely productive years with Impulse, the saxophonist typically generated a new album every four months.) The half year between recording sessions may well have bought Trane the necessary time to nurture and refine the suite. Those extra months may have been all the more valuable considering Coltrane’s workaholic gigging. Coltrane’s son, Ravi, explains that the quartet, criss-crossing the country, played 45 weeks a year, six nights a week, and three sets—sometimes four on weekends. For Coltrane the composer, there were no academic sabbaticals, no MacDowell colony. At the same time, the quartet’s venues—jazz clubs populated in part by noisy, inattentive patrons in pursuit of their own nonmusical nocturnal missions—were becoming less and less conducive to Coltrane’s spiritually motivated compositions and extended improvisations. Kahn notes that Coltrane waited until Antibes for A Love Supreme’s only performance because he considered the suite inappropriate for club consumption. The breakup of the great quartet at the end of 1965 dovetailed with Coltrane’s increasing liberation from his music’s tonal moorings. He could now plunge into a supercharged intensity level from the get-go. Why mess around with even token tonality when you can jump start your playing right into the ether? In Ascension and other late works, it is as if Coltrane’s point of departure was analogous to that supercharged moment two-thirds of the way through A Love Supreme’s Pursuance, when he had let everything hang out. In Pursuance, however, the listening experience remains informed by the suite’s previous travels. Pursuance is about freedom, but temporary freedom from a structure that remains etched in the listener’s memory. Everything we know about Coltrane’s final years from his music and his interviews points to the near certainty that he had more than his share of consciousness-expanding religious experiences. In the arts, this can be a double-edged plowshare. If you can see the face of God in a grain of sand, why bother to build beautifully structured sand castles? And if you are compassionate and generous, why not mentor younger players who share your passion for musical liberation, though neither your musical genius nor chops? In that musical area code, prospects for creating a successful analog to A Love Supreme indeed grow slim. But the explanation for A Love Supreme’s singularity may well be far simpler. John Coltrane may have been driven from the core of his being to compose his great suite as a recapitulation of his personal struggles and deliverance—and as an impassioned expression of gratitude to his Deliverer. We have the Verve Record Group and especially Ashley Kahn to thank for our renewed interest in these speculations and in one of the Twentieth Century’s great works of genius. |

Davis Masterpiece, you’ll

welcome his Coltrane study as more of the same. Like its predecessor,

Kahn’s latest sets the table by chronicling the artist’s career

leading up to the book’s central subject. It takes you into the

studio, reconstructing the album’s creation in take after take. It

casts close, perceptive analysis on the music itself. And it examines

the album’s impact on the participating artists, and the wider worlds

of music and culture. Both books offer fascinating tangential material.

Sidebars in the present volume chronicle the saga of Impulse records

and paint a biographical sketch of the legendary jazz recording

engineer, Rudy Van Gelder. Just as striking, both books are loaded

with archival eye candy. Their splendid photographs will no doubt keep

both volumes off the used book shop shelves.

Davis Masterpiece, you’ll

welcome his Coltrane study as more of the same. Like its predecessor,

Kahn’s latest sets the table by chronicling the artist’s career

leading up to the book’s central subject. It takes you into the

studio, reconstructing the album’s creation in take after take. It

casts close, perceptive analysis on the music itself. And it examines

the album’s impact on the participating artists, and the wider worlds

of music and culture. Both books offer fascinating tangential material.

Sidebars in the present volume chronicle the saga of Impulse records

and paint a biographical sketch of the legendary jazz recording

engineer, Rudy Van Gelder. Just as striking, both books are loaded

with archival eye candy. Their splendid photographs will no doubt keep

both volumes off the used book shop shelves. Chambers, at the

end of Blue in Green during a Kind of Blue studio

session.

Chambers, at the

end of Blue in Green during a Kind of Blue studio

session. Next, in a seamless

passing of the incantory musical baton, the saxophonist’s

double-tracked voice repeats A Love Supreme for about twenty

seconds until Acknowledgement’s end.

Next, in a seamless

passing of the incantory musical baton, the saxophonist’s

double-tracked voice repeats A Love Supreme for about twenty

seconds until Acknowledgement’s end.