For

nearly two hours on a Tuesday evening in February, Malian guitar

virtuoso Habib Koite and his six-piece unit, Bamada, brought a level

of ensemble mastery to Memorial Hall in Shelburne Falls,

Massachusetts, that would have been the envy of any world class

chamber group. The sold-out performance was part of the eclectic

Hilltown Folk series, which increasingly draws folk and world

music headliners to the upper Pioneer Valley. At concerts of

predominantly amplified instruments and voices, I consider it just

short of miraculous if the sound gets tolerably balanced within ten or

fifteen minutes. From the beginning, Bamada’s balance was impeccable,

offering crystal-clear definition to each instrument’s personality and

their polyrhythmic conversations. With hindsight, I shouldn’t have

been surprised—polyrhythmic and textural clarity are central to Koite’s musical agenda. For

nearly two hours on a Tuesday evening in February, Malian guitar

virtuoso Habib Koite and his six-piece unit, Bamada, brought a level

of ensemble mastery to Memorial Hall in Shelburne Falls,

Massachusetts, that would have been the envy of any world class

chamber group. The sold-out performance was part of the eclectic

Hilltown Folk series, which increasingly draws folk and world

music headliners to the upper Pioneer Valley. At concerts of

predominantly amplified instruments and voices, I consider it just

short of miraculous if the sound gets tolerably balanced within ten or

fifteen minutes. From the beginning, Bamada’s balance was impeccable,

offering crystal-clear definition to each instrument’s personality and

their polyrhythmic conversations. With hindsight, I shouldn’t have

been surprised—polyrhythmic and textural clarity are central to Koite’s musical agenda.Fronted by

Habib’s beguiling voice and his nuanced, amplified acoustic guitar

work, Bamada—which means mouth of the crocodile—also featured the

73-year-old virtuoso Keletigui Diabate on violin and balafon—a

wooden-key African cousin of the xylophone. The other musicians were Boubacar Sidibe on guitar and harmonica, Abdoul Wahab Berthe on

electric bass, Souleymane Ann on Western drum kit and calebas se

(calabash), and Mahamadou Kone on talking drum and a grab bag of

percussion instruments. se

(calabash), and Mahamadou Kone on talking drum and a grab bag of

percussion instruments.

From Bamada’s first note, polyrhythms ruled

the day. This is one extraordinary polyrhythmic machine, I told

myself. But the machine metaphor didn’t do the band justice, because

its interplay was utterly organic. In that seamless cohesiveness,

Koite’s own musical personality was central. From his dreads-in-motion

image on posters and cds, you’d expect a wild and crazy stage

presence. Not for a moment. On stage, he was humility incarnate,

providing through leadership and musicianship the unifying force that

kept Bamada’s musical ingredients in sync.

Koite’s characterization by publicists as the

African Eric Clapton is more marketing invention than musical

reality. Like Clapton’s guitar work , Habib’s was technically

masterful and nuanced, but the similarity ended there. Clapton crafts

lengthy lines that move toward harmonic-rhythmic payoffs. Koite’s

largely nonlinear approach dwelled within each chord, exploring

its anatomy through ingenious combinations of rhythms, trills, and

note juxtapositions. In addition to traditional Malian motifs, Koite’s

playing incorporated stylistic ingredients from flamenco, Afropop,

samba, and American jazz and blues. But his guitar lines rarely

resolved according to Western harmonic expectations. Instead they

found resolution through fleeting melodic riffs that often dovetailed

with ingenious intersections of rhythms, timbres, and dynamics.

Koite’s gorgeous three-octave voice was no

less distinctive. With the burnish ed

quality of teak or rosewood, it consistently emerged from Bamada’s

instrumental fabric, leading the band forward. And it drew periodic

vocal responses from other band members, who sang in unison or one-

and two-step intervals. ed

quality of teak or rosewood, it consistently emerged from Bamada’s

instrumental fabric, leading the band forward. And it drew periodic

vocal responses from other band members, who sang in unison or one-

and two-step intervals.

On balafon and violin, seventy-something

Keletigui Diabate was the band’s big improvisational risk taker. His

playing packed more linear punch than the leader’s. At the same time,

Diabate piled up notes vertically in inventive rhythmic combinations.

Three-quarters through one of his too-infrequent violin solos, Diabate

joined forces with Koite in an improvisational duet with Habib

perfectly echoing his senior’s increasingly complex phrases. The

escalating energy was a high point of the concert. Another galvanizing

presence was the percussionist, Mahamadou Kone, who employed a curved

wooden beater to produce riveting percussive accents (including

elastic changes in pitch) from a talking drum. At times, the mercurial

Kone bounded about the stage, stoking the energy levels of the other

musicians.

By blood line and vocation, Koite is a

griot—a Malian song-story teller who musically transmits Malian

cultural myths and history. That history spans centuries and

encompasses dynasties of former monarchs who ruled what was once one

of west Africa’s most powerful kingdoms. Many griots were court

musicians who deployed bardic song to celebrate the kings, their

ancestors, and Mali’s rich cultural traditions. Koite’s music

continues that exploration and current topics like urbanization and

the evils of cigarettes. Few in the hall, of course, had a clue about

what Koite was singing. But no one seemed to mind. Bamada’s energy

level and ensemble playing were continuously compelling.

Koite and Bamada share exalted company with

fellow Malian Rokia Traore, who like Bamada combines traditional and

modern elements with exquisite ensemble playing. When I heard Rokia

and her band at the Iron Horse in Northampton, Mass. several summers ago, I was bowled over.

For me, their ensemble work and strategic deployment of every musical

element was revelatory. This is a fresh, new aesthetic, I told myself,

that stands with the best music-making that any culture or genre has

to offer. On February 1st in Shelburne Falls,

it

was a blessing to revisit that aesthetic through the inspired

performance of Habib Koite and Bamada. it

was a blessing to revisit that aesthetic through the inspired

performance of Habib Koite and Bamada.

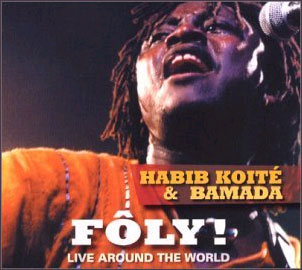

The next best thing to being there is hearing

Koite’s double record concert cd-Foly! Live around the World-on the

World Village label. The disc’s eighteen tracks offer unabridged

performances, many of which exceed ten minutes. And Foly! is priced at

two discs for the price of one.

For an illuminating, entertaining audio

introduction to Mali’s diverse, dynamic music, listen to Lucy Duran’s

BBC presentation via the following link:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/world/guidemali.shtml

|